2014 was pretty exciting for photography enthusiasts, with many new lenses and cameras being released at Photokina towards the end of the year. As we begin 2015, all the excitement is now focused on the high-end segment of the consumer market, which is where most of the innovation seems to be happening.

For the past few years, mirrorless interchangeable-lens cameras (MILCs) have been shaking things up and challenging DSLRs in terms of image quality and features with great success. Now, they’ve finally reached the tipping point: they’re so good that many pros are switching over to MILC setups and never looking back.

This year, though, we’ve witnessed the arrival of a few truly excellent fixed-lens compact cameras that are challenging their interchangeable-lens siblings for the first time. Let’s take a moment to think about the current landscape, and see if these newcomers have what it takes to make a difference.

But first, let’s take the obvious out of the way: there are no bad cameras or lenses out there anymore. That’s a fact. It is extremely likely that whatever camera you already own is perfectly capable of taking really great pictures, if you take the time to learn how to use it. So be advised: a “better” camera will not magically make you a better photographer. If you’re happy with what you already own, just keep it, stop reading now and go take some awesome pictures. This is all just splitting hairs, really.

Mirrorless Interchangeable-Lens Cameras (Crop Sensor)

For many enthusiasts and even some professional photographers, MILCs are a great alternative to full-blown DSLRs. They offer an amazing compromise between features and portability, and they’ve recently taken the world by storm.

The big players here are Panasonic, Olympus, Fujifilm and Sony. They all offer great cameras, stellar lenses and similar price points, so choosing between them becomes mostly a matter of picking the sensor size and dedicated features that better match your personal shooting style.

Olympus OM-D E-M1 with 12-40mm f/2.8 PRO lens vs Nikon D800 with the comparable 24-70mm f/2.8 zoom lens. The difference in size and weight is remarkable. Photo Credit: Cajetan Barretto.

Olympus and Panasonic both make Micro Four Thirds cameras (M4/3), which use a sensor with a crop factor of 2. This means the field of view of its lenses is roughly equivalent to a full-frame lens with double the focal length. For example, the field of view of a 25mm M4/3 lens is the same as that of a 50mm full-frame lens. By comparison, the slightly bigger APS-C sensor used in Fujifilm and Sony MILCs has a crop factor of 1.5, so the field of view of a 23mm Fuji lens would be equal to that of a 35mm full-frame lens.

Another thing to consider is that the M4/3 system specification includes the lens mount, whereas APS-C only refers to the sensor size. In practice this is very important, because it means Panasonic and Olympus cameras can share lenses between them without the need for adapters of any kind, something that is not possible between Fuji and Sony cameras, as they each use a different proprietary mount with their APS-C sensors.

The best cameras in this category are currently the Panasonic GH4, the Olympus OM-D E-M1 and the Fujifilm X-T1. All three have professional-grade bodies and features, and retail for roughly the same price.

Lens-selection is also excellent for all three of these cameras. The past few years have been incredible for the M4/3 system, with the release of some really amazing lenses like the Panasonic Leica 25mm f/1.4 (50mm full-frame equivalent), the Panasonic Leica 42.5mm f/1.2 (85mm full-frame equivalent), and the Olympus M.Zuiko 75mm f/1.8 (150mm full-frame equivalent).

With some excellent lens releases in 2014, Fujifilm is not lagging behind, though. Fuji XF lenses are just as good as the M4/3 offerings, and their lineup now boasts a complete set of fast primes, including the Fuji XF 23mm f/1.4 (35mm full-frame equivalent), the Fuji XF 35mm f/1.4 (53mm full-frame equivalent) and the Fuji XF 56mm f/1.2 (85mm full-frame equivalent).

With such variety of great lenses to choose from in both systems, it really comes down to which one feels better for you, personally. If you want smaller and lighter lenses and bodies, you’ll feel right at home within the M4/3 ecosystem. If you want to take advantage of the better low-light capabilities and shallower depth of field of the bigger APS-C sensor, Fuji is what you want to get.

For the more budget-oriented customer, the same companies offer some fantastic entry-level — but full-featured — bodies, like the Panasonic GX7, the Fuji X-E2, the Sony Alpha a6000 and the Olympus OM-D E-M10, which is my current camera. These will get you many of the same features and image quality as their more expensive siblings, except for a few pro-oriented features like weather sealing, 5-axis in-body image stabilization, and the like. They’re perfectly capable of taking images which are just as great, at a fraction of the cost. In my mind, these offer much better value for the money, and unless you’re a serious enthusiast or professional shooter, I’d put the difference towards buying a couple nice lenses instead.

That said, as you get better and learn more about photography and your camera, you will start looking towards the high-end models. It may be a case of legitimate need, or it may simply be that you’ve fallen victim to Gear Acquisition Syndrome. Don’t worry, it happens to the best of us. In these cases, my advice is to use the two-week test and see if that helps. If you pass the test and still decide to go for it, then great! These are amazing cameras and they do offer several genuinely useful features you won’t find on the entry-level models, so it will be money well spent.

Fixed-lens digital cameras

They could be mistaken for point-and-shoots at a glance, but there’s plenty more substance here. These are serious cameras in every way, in many cases just as good or even better than many MILCs, except for one thing: the lens is permanently attached to the camera body, and as such cannot be changed.

All major players have cameras in this category. Notable mentions include the Panasonic Lumix LX100, the Canon PowerShot G1X Mk II and the Sony RX100 III.

These are all excellent cameras with plenty of high-end features but to me, the most interesting camera by far in this space is the new Fujifilm X100T. While the Panasonic, the Canon and the Sony all try to offer a no-compromises zoom lens with varying success, the Fuji truly embraces its single-focus nature with a gorgeous prime lens that sets it apart in terms of image quality.

The Fujifilm X100T is the most interesting fixed-lens camera available right now. Photo Credit: Daniel Go.

This camera has the same APS-C image sensor found in its more expensive interchangeable-lens sibling, the X-T1, and many of the characteristic features Fuji fans love, like dedicated exposure compensation and shutter speed dials on the body, as well as an aperture ring on its built-in 23mm f/2 lens, which is equivalent to a 35mm full-frame focal length. This lens is tack sharp, fast and it’s capable of taking some really awesome pictures. Unlike the others though, the Fuji X100T has no optical zoom, so you’ll really need to get used to the 35mm equivalent focal length (which is awesome, but more on that later).

If you’re in the market for a fixed-lens camera, the Fuji X100T is about as huge a no-brainer as it gets. Plain and simple.

A quick aside about full-frame digital cameras

Many of these comparisons also apply to the full-frame world. Indeed, the Sony RX1R is remarkably similar to the Fuji X100T, only equipped with a full-frame sensor. And then there’s the Sony A7 series, which are full-frame MILCs that promise all the benefits of DSLRs with the convenience of small, mirrorless bodies. Not to mention Leica, of course.

All of these are terrific cameras, but they’re significantly more expensive: the Sony RX1R costs about $2,800, while the current-generation Sony A7 Mk II with a 55mm prime lens will run you a cool $2,700. And Leica is… well, Leica. These cameras are clearly not aimed at typical shooters and are more oriented towards the very high-end enthusiast and pro markets. At this point though, they’re also competing with full-blown DSLRs from Canon and Nikon and, while the gap is narrowing quickly, those are still preferred by many professional photographers, particularly for their superior ability to capture fast action shots, sports, etc.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m absolutely convinced that mirrorless is the future of photography, and that DSLRs will slowly continue to lose appeal for the vast majority of shooters. If I were a professional photographer today, I’d be extremely tempted to get the Sony A7 Mk II, and I’m willing to bet in just a few years, DSLRs will be relegated to a very small niche of professional shooters for whom nothing else will do — and even they will be conquered eventually. It’s clearly just a matter of time, but unfortunately we’re not quite there yet.

Choose your poison

The arrival of great fixed-lens cameras like the Fuji X100T has many people wondering if we really need interchangeable lenses anymore. It’s a fair question, but to me it’s ultimately misguided. Both systems are profoundly different, to the point that they’re hardly comparable.

The X100T has a lot going for it, starting with its choice of focal length. The only way I could be happy with a fixed-lens camera is if it had a 35mm (full-frame equivalent) lens, which is by far my favorite focal length. It’s incredibly versatile, perfect for street photography and environmental portraits, where you want to showcase a bit more of the scene along with your subject. You can do many different things with a 35mm lens, and do them really well. Indeed, it’s surprisingly easy to shoot great images in this focal length and many people, both newcomers and seasoned photographers alike, just intuitively “get it”.

You can take pretty cool pictures with a 35mm lens where you get to show a bit more of the scene, along with your subject. All pictures: Canon AE-1 Program with Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens and Kodak Portra 400 film.

The 35mm perspective is perfect for capturing city landmarks, which wouldn’t fit in the frame with longer — and therefore, narrower — lenses. All pictures: Canon AE-1 Program with Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens and Fuji Superia 400 film.

But there are other ways to shoot in this focal length, besides the X100T. Fujifilm itself has the gorgeous Fuji XF 23mm f/1.4 lens for their X-line cameras, which renders the same perspective and is even faster than the built-in lens of the X100T. If I didn’t own a camera today, this lens would almost be enough to lure me into buying the Fuji X-E1 or even the X-T1 instead of my E-M10.

Unfortunately, support for this focal length in the M4/3 ecosystem kind of sucks. I didn’t appreciate this when I purchased my E-M10 because I didn’t really fall in love with the 35mm length until later on, when I started shooting with my father’s Canon AE-1 Program and a Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens.

The lack of a proper 35mm-equivalent fast prime lens is probably the single sore spot left in the M4/3 system. As of this writing, the only choices are the Olympus M. Zuiko 17mm f/1.8, which is fine but not stellar, and the Voigtlander Nokton 17.5mm f/0.95, which is an amazing lens but costs twice as much as the E-M10 itself and is manual-focus only. I’d love to see a 17.5mm f/1.4 lens from Panasonic/Leica, but it doesn’t look like it’s going to happen anytime soon.

Canon AE-1 Program film SLR with Canon FDn 50mm f/1.8 lens and Olympus OM-D E-M10 Micro Four Thirds camera with Panasonic Leica 25mm f/1.4 lens.

However, as versatile as the 35mm focal length is, it’s not the end-all, be-all of photography, and that’s where the strength of interchangeable-lens systems begins to show.

Enforced creativity

You clearly don’t need to carry six different lenses every day to take nice pictures, and it’s true that sometimes, adding constraints is a great way to fuel creativity and evolve as a photographer. Some massively successful services like Vine or Twitter were built on the very principle that setting an artificial limit — 6 seconds per video, 140 characters per tweet — ultimately leads to better content because it makes us think before we post. It makes us worry about making every word or every second count, and that’s when the magic happens.

However, I don’t think limiting yourself to only one focal length is a very good analogy to this principle. A better one would be shooting in manual mode only. Or shooting film with an all-mechanical camera. Both approaches will force you to think a great deal before pressing the shutter release button. Is my shutter speed correct for the motion I want to convey? Will this aperture give me an adequate depth of field? Is my subject in focus? Is my exposure correct? These are all essential questions that we take for granted every time we grab a camera with full-autoeverything and fire away in bursts of 10 shots per second, hoping that one of them will come out halfway decent.

It all boils down to giving a shit.

When you give a shit, you wonder about your composition, and about the light. You consider if your subject is comfortable, or if the situation feels forced. You take into account the nature of the shot, and whether you want to isolate your subject or integrate them within the scene. You do all this before even coming close to touching the shutter release and in the end, it shows. Comparatively, I get many more keepers when I shoot film because with film, everything is arranged in a way that forces me to slow down and think. I also know I have a limited resource — only 36 frames per roll — which motivates me to try and make every shot count.

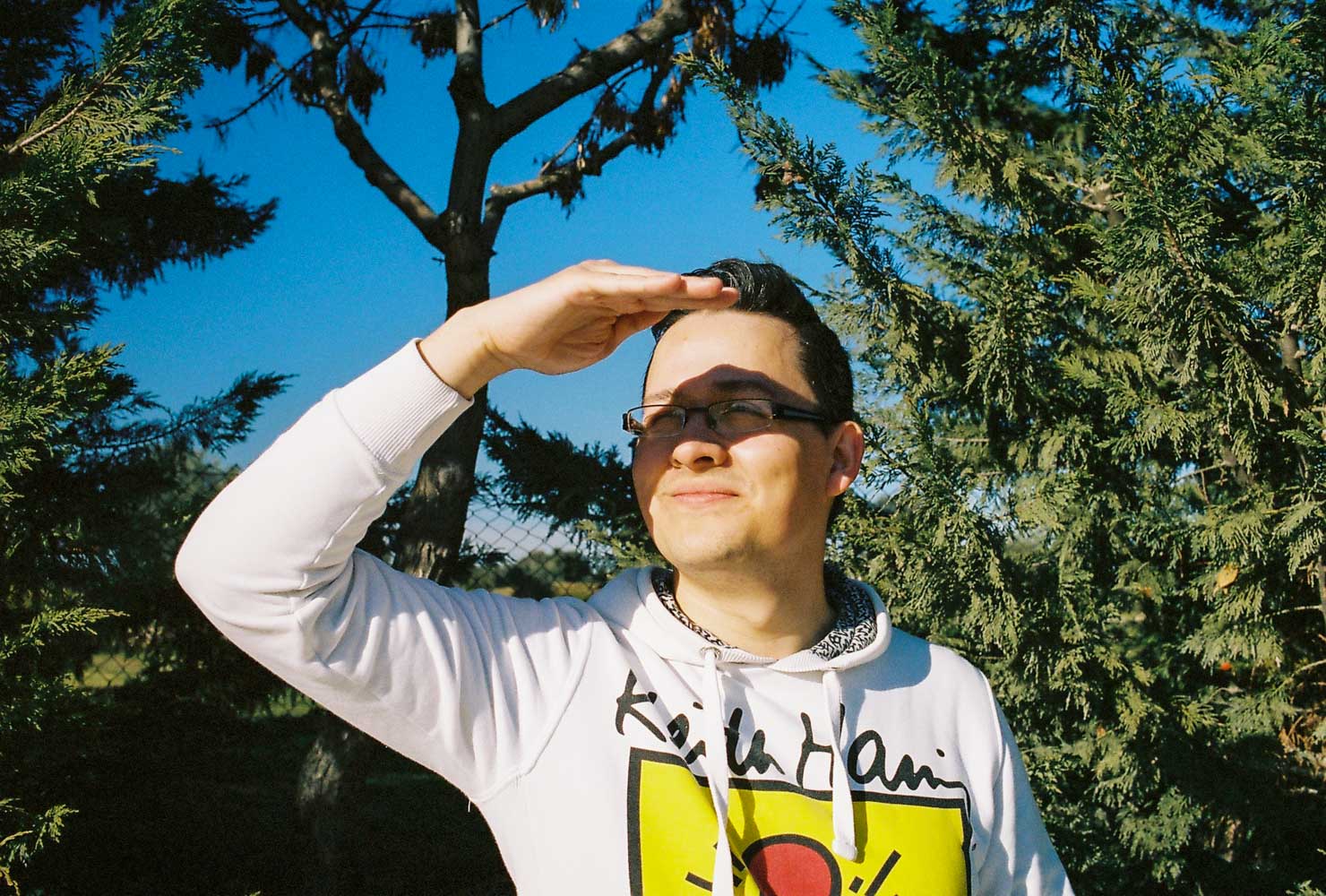

When your subjects are relaxed it’s a lot easier to capture fun or spontaneous moments. All pictures: Canon AE-1 Program with Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens. Top two: Kodak Portra 400 film. Bottom: Fuji Superia 400 film.

By doing this, you’ll be able to get amazing shots with almost any camera, and any lens. You’ll be able to adapt your technique to the lens you’re using, and you’ll learn to use the lens up to its full potential.

But if you limit yourself to a single focal length, there are some things you’ll never be able to do.

Jack of all trades

One of the most sought-after effects in modern digital photography is the shallow depth of field, where only a smart portion of the scene is in focus and the rest is blurry. The quality of the out of focus areas is called bokeh which, when it’s good, is usually described as “creamy”.

Bokeh is the word that describes the out of focus areas. E-M10 with Panasonic/Leica 25mm f/1.4 lens at f/1.4

The amount and quality of bokeh depends on several elements like sensor size, lens speed and yes, focal length. Getting tons of bokeh with a 35mm lens is pretty difficult, particularly with a crop sensor camera like the Fuji X100T. That’s just how optics work, and there’s no way around it. Of course, this is not an absolute statement: you can create some amount of bokeh with the X100T, and it will look fine. If that’s enough for you then awesome, but if you really want to achieve subject separation with lots of gorgeous, creamy bokeh, your best bet is to go with a long, fast lens and ideally, a full-frame sensor.

This is about as much bokeh as you can realistically expect from the 35mm focal length. It’s not bad by any means, but it’s not spectacular either. Canon AE-1 Program with Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens at f/2 and Kodak Portra 400 film

Another issue with short focal lengths — 35mm or less — is perspective distortion. A very common expression in favor of fixed-lens cameras is to say that you can always “zoom with your feet”. By stepping closer to your subject you can reduce the amount of scene that will fit in the frame, and the effect is similar than if you had taken the shot with a longer lens. This approach usually works, but is somewhat limited. As you step closer and closer to your subject, perspective distortion starts being noticeable, and it’s more pronounced the closer you are to your subject and the shorter and wider the lens is. Another way to achieve a similar effect is by using a wider lens and then simply cropping to reduce the field of view.

You can reasonably mimic a 50mm field of view with a 35mm lens by cropping or stepping closer to the scene, mainly because there’s not much difference between the two to begin with. However, mimicking a longer lens becomes more difficult due to perspective distortion.

These images show how it’s possible to mimic a 50mm field of view by cropping a picture taken with a 35mm lens. Notice the difference in bokeh: all other things being equal — both lenses are stopped down to f/2 — the longer lens has noticeably better bokeh. All images: Canon AE-1 Program camera and Fuji Superia 400 film. Top: Canon FDn 50mm f/1.8 lens at f/2. Middle: Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens at f/2, cropped to mimic a 50mm field of view. Bottom: Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens at f/2, complete frame.

The difference between the field of view of a 50mm and a 35mm lens is small, but it’s enough to matter when shooting city landmarks. Both images: Canon AE-1 Program and Fuji Superia 400 film. Top: Canon FDn 50mm f/1.8 lens at f/8. Bottom: Canon FDn 35mm f/2 lens at f/8.

Portrait lenses are usually long because with the longer focal lengths, perspective distortion is barely noticeable and people look more natural. By comparison, a close-up portrait shot with a wide-angle lens looks weird and the results are often not very flattering. Also, it’s much easier to achieve subject separation and bokeh with a long lens, which is a great way to make your subject “pop” from the background. In my mind, the minimum acceptable length for portraits is 50mm, and the sweetspot is in the 85mm-150mm range.

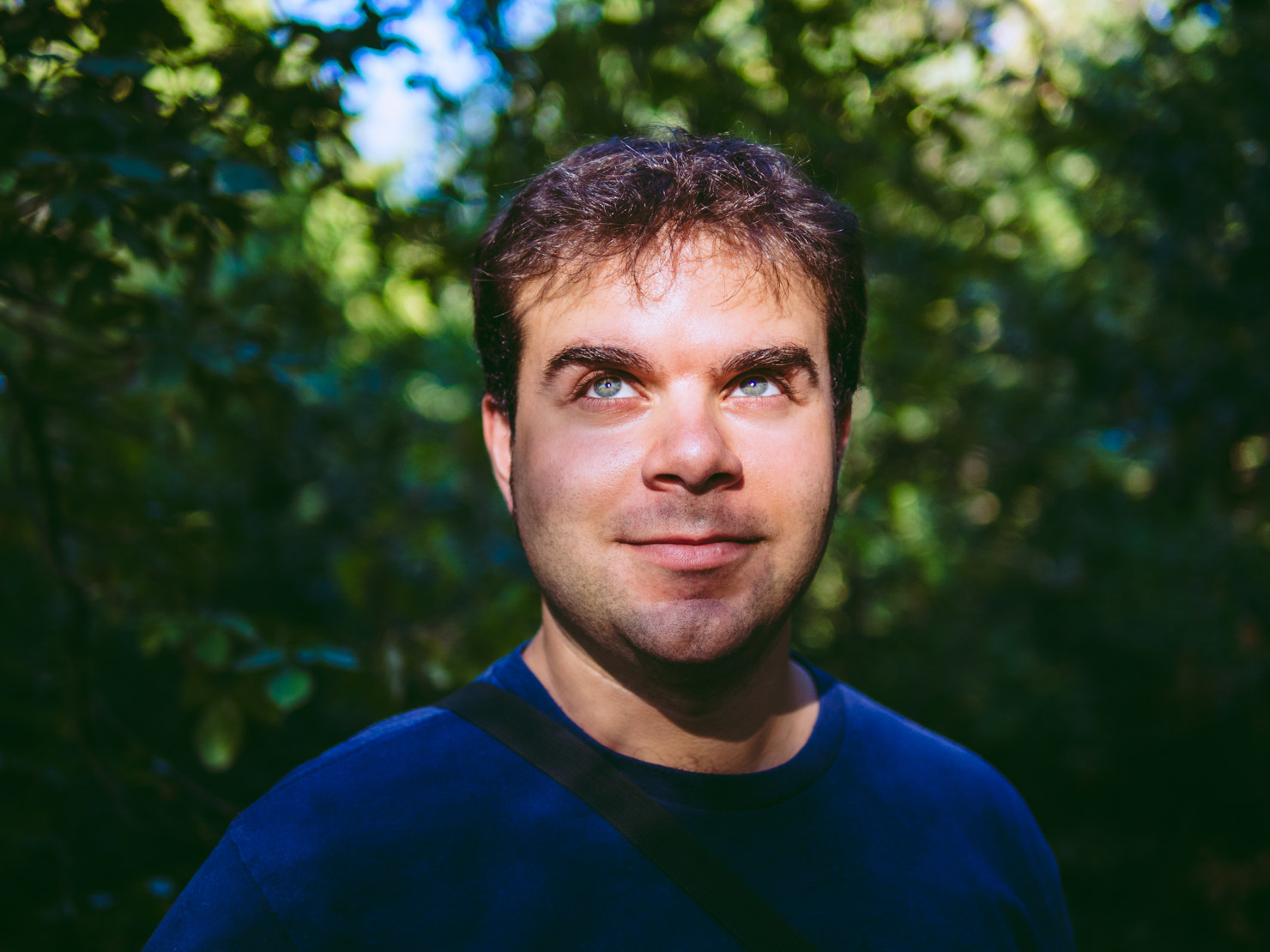

These portraits were all taken with an Olympus E-M10 and the Panasonic Leica 25mm f/1.4 lens, which is equivalent to a 50mm full-frame length. Anything shorter than this, and portraits start to look weird due to perspective distortion.

Bokeh and perspective distortion are two of the most important differences between longer and shorter lenses, but perhaps the biggest reason not to limit your photography to only one focal length is that, over time, all of your compositions will start to look very similar. This can be a good thing, if you’re a creative photographer trying to develop a signature style, but if you want to learn composition or add some variety to your shots it’s hardly the best way to go.

There is no wrong answer

I’m a big believer in prime lenses and MILCs, but I understand they are not for everyone. Likewise, I can appreciate the many benefits of fixed-lens cameras like the Fuji X100T, even if they’re not up my particular alley.

A fixed-lens camera is an amazing tool to carry when you want to document life, trips or just enjoy the pleasure of taking pictures. By taking a few choices off your hands, the entire process is simplified, and therefore more accessible and enjoyable. These machines are perfect for creating wonderful memories, and you’ll never regret buying one. In my mind they are reminiscent of fixed-gear bicycles: objectively more limited than multiple-gear bikes, but just so damn fun.

Interchangeable-lens cameras, on the other hand, put all the options in your hands, to do with what you will. If you’re into product photography or want to experiment and create several different looks in your images, you’ll need the benefit of additional lenses. Buying into one of these systems is an investment that will give you ample room to grow and learn. If you still don’t know what kind of photographer you want to be, this is how you’ll find out.

Whatever you decide in the end, the key is to be patient, and persevere. As with many things in life, in photography practice makes perfect, and there’s no substitute for it. It can take a long time to develop your photographic vision, and making mistakes is the only way to move forward.

I know I’m making it sound difficult but trust me, you really wouldn’t want it any other way. Hell, after a year shooting every day I’m still a beginner, by any reasonable definition of the word. I make mistakes every single time I pick up a camera and for each thing I’ve learned, there are a hundred more I still haven’t figured out. So stop worrying so much, grab your favorite camera and step out your front door.

Because, after all, that’s where all the fun is.

This is me. Hi. Canon AE-1 Program film SLR with Canon FDn 50mm f/1.8 lens and Kodak Tri-X 400 black and white film.